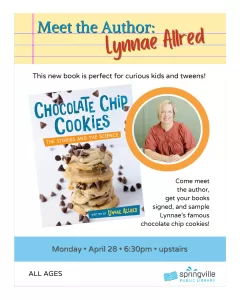

Last weekend, I had the painful privilege of helping my Mom and several of my siblings clean out my Dad’s woodshop. He died almost four years ago, but here, in this space, memories of him are still palpable. His old insulated coveralls hang against the wall. They still smell like him. His collections of wood-turning books are full of drawings and notes in his handwriting. And here is an old set of headphones plugged into his cassette tape recorder. He was constantly listening to books on tape—mostly religious addresses he listened to in his quest to become a better man.

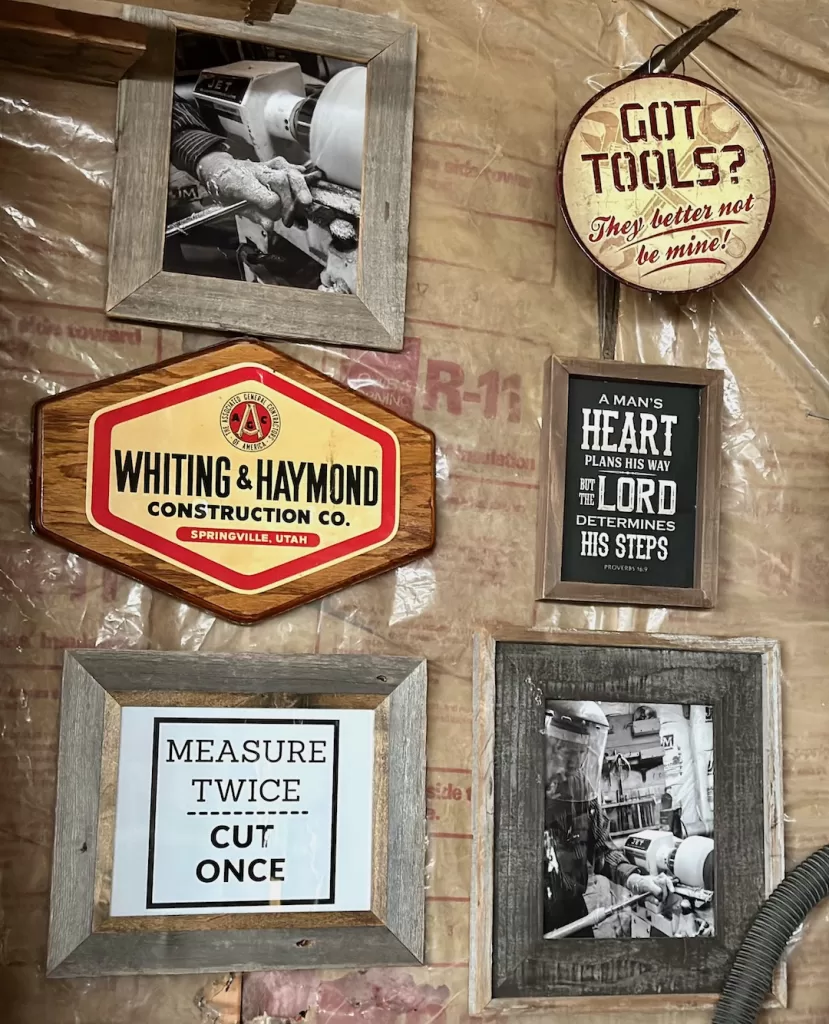

And his tools. So. Many. Tools!

Dad’s workshop has been his respite all of his life, even though it had to migrate and evolve over the years as his growing family took up more and more space. Somehow, he always managed to preserve a corner world where he could enjoy his hobbies and create. My Dad might be surprised to hear me calling him a creative person, but he had a fascinating ability to turn a photo or a drawing into a tangible item.

If Mom wanted a china cabinet, or a gazebo for her garden, or a rose trellis, he would say, “Draw me a picture.” She didn’t draw but had visions in her head and a subscription to Better Homes and Gardens Magazine. Photos were no problem. It was his task to create treasures from nothing but a phantasm.

He did practical work, too. He built a contraption that would seal off the leaking irrigation pipes. He crafted elaborate hanging systems to organize the broom, dustpan, and extension cords when a 2-dollar hook from Walmart would have done the job. Sometimes, he disguised his play as work by creating in this way. It allowed him to retire to his pondering spot. The smell of sawdust was aromatherapy. He could cope with the stress of his regular workday by unwinding with a pipe organ concert blaring through his headphones while he dozed in an old office chair, his whittling pocketknife still in his hands. Mom had walls to be torn down, fences to install, and hot tub decks to stain. But first, he would carve her a rose out of a slab of dark walnut.

My Earliest Memories of Helping in the Shop

My very earliest memories are of watching Dad in his shop with a hand plane, shaving a piece of wood smooth so that he could build something for Mom — a decorative shelf in the corner of the kitchen above the sink where she could display African violets, or treehouse steps to nail into the side of the Box Elder tree so my brother could build his longed-for treehouse. I loved the smell of wood and the curly shavings the plane left on the floor among the sawdust under Dad’s table saw.

I have memories of sitting on the floor sorting screws for him — a job he would give me to keep me out of trouble while he worked. He didn’t invite me to the shop to teach me his craft. Woodworking was men’s work. I was an adult before I realized that it was a gender distinction I disagreed with. Eventually, I convinced him to teach me, but by then, his hands were slower and more twisted, and my life was busy. To show for my efforts, I have a cedar bowl carved from the limb of a tree his great-grandfather planted and a precious pen turned on the lathe from a branch of apricot wood. My younger sisters were more successful, and two of them have a facility with a chop saw and a Dremel that I envy.

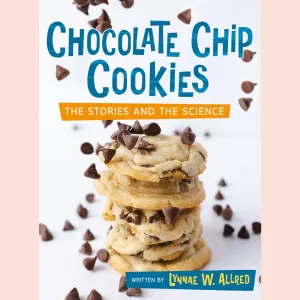

Dad’s hands cutting wood blanks we would later use to turn pens on the lathe.

Working in the Darkroom with Dad

But I spent many hours in the shop helping with other small tasks. Dad was an amateur photographer, so one of my favorite jobs was standing by with a pair of tongs while developing film. I’d push the photographic paper into the developer, and then the stop bath, and then the fixative. Black and white photos magically appeared on the white paper.

For many years, Dad had a side hustle fixing the components of “flasher barricades” used on the highways to warn drivers of a construction zone. He could make a dollar for every flasher he could repair. I’d stand there with him while he tinkered with the components, replacing bulbs or repairing wiring so that the little boxes would flash again. This, so there would be a little extra cash in the budget to rent a violin for me. His schoolteacher’s salary didn’t stretch far enough to give nine children all the opportunities he and Mom wanted us to have. This project helped bridge the gap.

Facing the Daunting Task of Letting Go

All this is to say that we put off clearing out the shop after his passing, not simply because it was a daunting task, but because doing it meant facing the finality of him being gone.

The attic above Dad’s workshop became the storage site for extra parts that might come in handy some day.

Ultimately, the solution came from my sister, Marilee, who is NOT sentimentally attached to cast-off plumbing parts or extension cords missing the plug end. She bought a plane ticket and came the weekend of the great cleanup to help. She took one look at the attic where Dad had been storing carefully organized containers of nuts, bolts, leftover insulation, painting drop cloths, a 40-year supply of caulk, and logs salvaged from the apricot tree and immediately hired a burly man to deliver a 25-foot dumpster; she offered him a tip if he could get it there by 7 a.m. the following morning.

And because Marilee is a trained therapist, she also had the generosity to understand that for some of us, the task was not so simple as tossing entire boxes of junk out of the window into the dumpster waiting below. She could say, “This is hard, isn’t it?” when she saw Mom’s tear-filled eyes. She knew it was important to hang onto the box of yellow metal toy excavators from Dad’s childhood, realizing that one of my brothers who IS sentimental would melt with joy to be given the privilege of adding them to his own attic.

And she allowed Mom space to rescue things like the boxed-up port-a-potty, old buckets that still had handles, and plastic tubs of rusting caulk guns to put outside by the street with a sign that said, “FREE” because surely some of those things still had value to someone. It is easier to let go of junk when we believe there are others who actually need it.

What to Hold Back, What to Let Go Of…

Mom gave each of her children the opportunity to claim a few tools, just in case any of us needed an extra screwdriver (Dad had dozens of them), or there was a memory attached to a specific red hammer with his initials on the handle.

The big red toolbox on wheels made a 570-mile trip to my brother’s house in Montana because she thought he’d appreciate it in his own recently acquired shop space. She insisted the antique tools that had belonged to my great-grandfather be preserved for another brother. We saved a box of scrap projects Dad had turned on the lathe and then abandoned. Maybe they will become Christmas tree ornaments if my resolve holds out. Or maybe they will go into the dumpster after Mom passes. My younger sister, who IS sentimental like me, will hang on to those just a bit longer.

Space for Living in the Present

At the end of the day, the dumpster and a full pickup truck overflowed. Inside were scraps of wood and salvaged handicap-accessible parking signs. There were piles of plastic Visqueen, thousands of used screws (that had been carefully sorted by size), and miles of electrical cords, each missing a plug end, that he had saved in case he ever got time to repair them. His books on tape, the filthy coveralls, still with mismatched leather work gloves in the pockets, and his sawdust-encrusted cassette tape player and headphones also went onto the pile. It is, after all, junk that will clutter up the spaces we need in our heads for living in the present.

My oldest brother, David, who had been on hand to assure Mom that “No, we won’t need these wood scraps or these half-sheets of plywood and sheetrock anymore,” jumped in the truck with me at the last minute as I drove the last load of paint and pesticides to a hazardous waste disposal site. I think he knew, somehow, that I needed his company on that final drive. I looked around at the waste management facility and marveled at the piles and piles of junk others had cast off that day. I ached a little at the idea that we take so much abundance for granted, and cast it off so easily.

But today wasn’t easy. It was dirty, filthy, aching, painful, cathartic work. The teenage grandkids are planning how to turn the empty attic into a hangout spot. Mom can easily park her car inside the garage. The lathe will stay here for the next generation to use for the time being. We saved pieces of apricot, walnut, and a small box of exotic mahogany and mesquite wood for making pens, just in case someone else wants to turn a memory on the lathe someday.

And I brought home a hand plane. It is on the shelf in the office where I work every day. Someday, my children will toss it in a dumpster, and their foreheads will crease in confusion about why I held onto the rusty old thing. But for now, it is a memory I can keep that I have space for. It will carry me back to the past in moments when the present is momentarily unbearable. And I will think of Dad and how he created a beautiful life for me with his tools, his wood, and his words.

Then I will set it down and get back to the work of creating.