Near the mouth of Price Canyon, two gigantic sandstone walls tower above the valley floor. As you travel east to approach the canyon, the walls appear to swing open like a giant gate. The optical illusion caused early settlers to name the place, Castle Gate, and in the 1880s, the Pleasant Valley coal company started mining operations in the area.

Castle Gate. Source: “Castle Gate, Price [Cañon].” Detroit Photographic Co., between 1898 and 1905. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.17820. Creator: Detroit Photographic Co.

As we drove past Castle Gate on a clear October morning, I thought about how both names, Castle Gate and Pleasant Valley, were cruel verbal illusions as well. For a first-time traveler, the gate does not protect anything pleasant. The valley is as barren and dry as any other central Utah desert town.

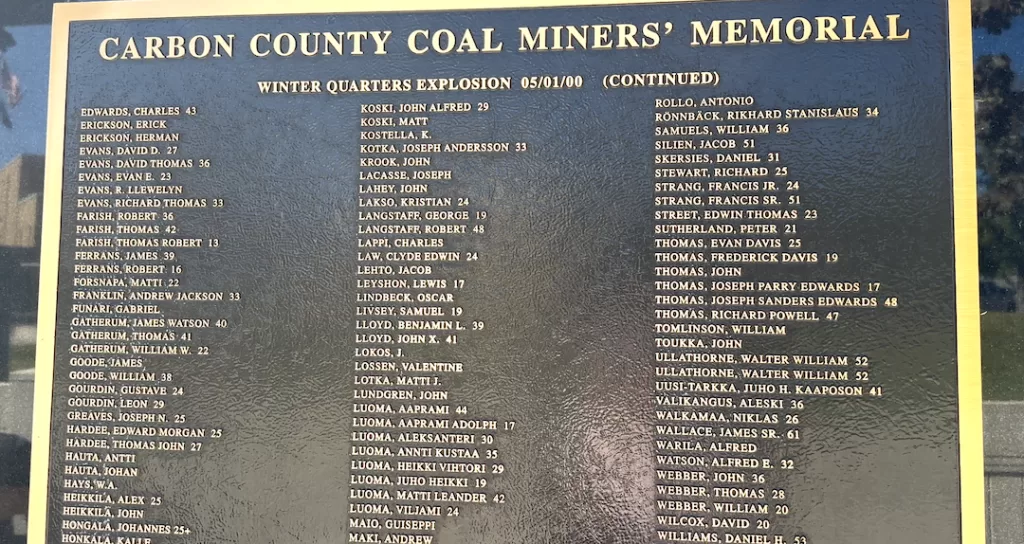

Indeed, once mining operations started in 1886, and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad built a track through the area, near-destitute miners came from all over the world to settle in the area and try to scratch out a living from deep underground. That didn’t go particularly well either. In 1924, a series of explosions at the Castle Gate mine killed 171 miners, making it among the deadliest mining disasters in US history. The town was closed and residents relocated, but even this disaster did not top others in the area. The Winter Quarters mine explosion a few miles further down the canyon had killed 200 men only 24 years earlier.

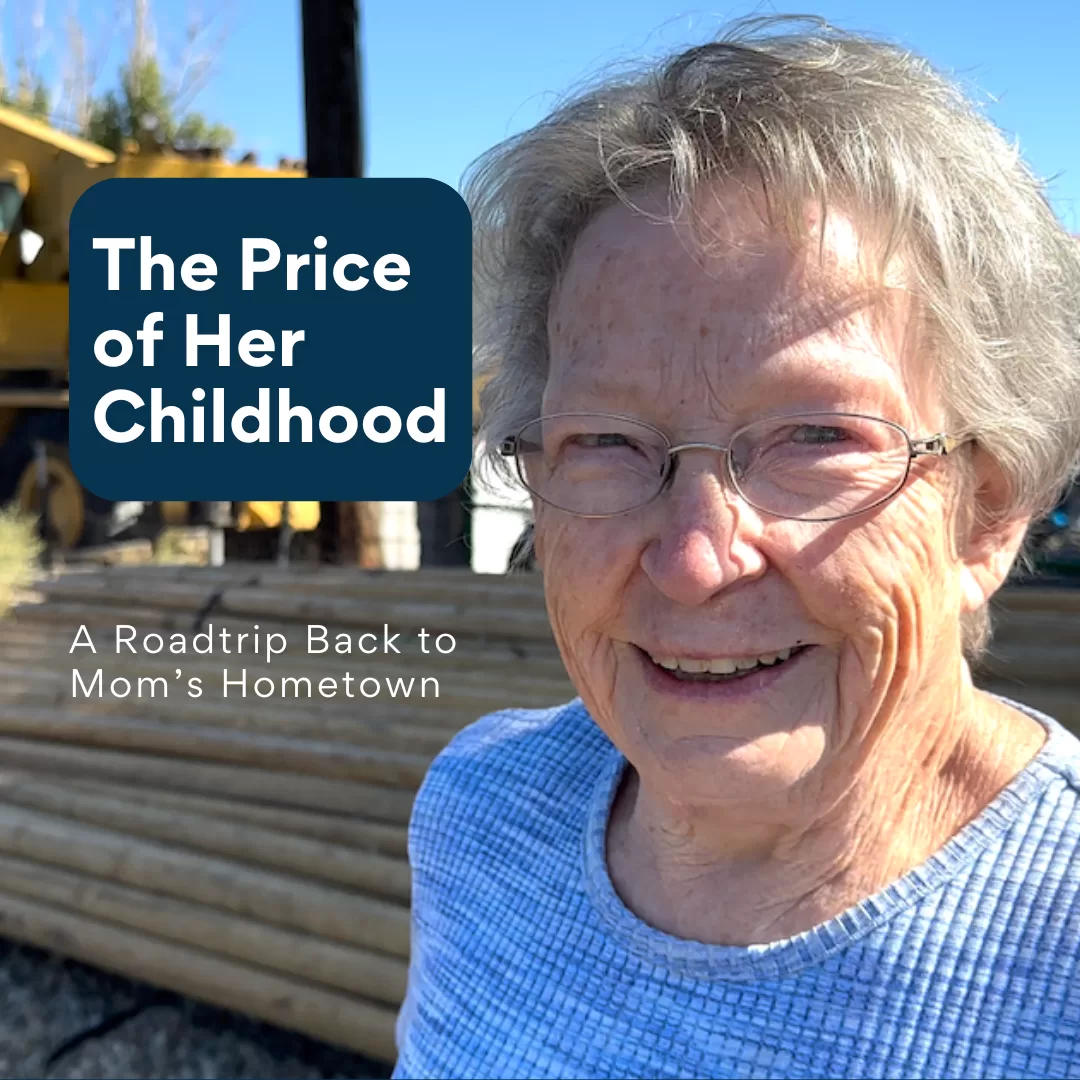

As we passed Castle Gate and drove into Price City that morning, my sister, Marilee, asked the first question: “What do these families do for a living, and why do they stay here?” We had come to bring our Mom, Joyce, back to her childhood hometown. We wanted to see what memories would bubble up for Mom because of this little excursion. We wanted to understand more about her roots by taking her back to the place where her earliest memories had formed.

Back Home to Price

Initially, there were no memories. So much had changed in the 70 years since her parents had left the little community that she couldn’t pick out any landmarks. She knew her home had been near the freeway entrance, nestled into a curve of railroad track, so we looked for and found both the freeway entrance and the tracks, but nothing fit her description of what the home had looked like.

Next, we drove closer to downtown, circling the area looking for any older buildings that might have existed in the 1940s. Eventually, one stood out: the bank. Joyce knew this was the bank on the corner of the street where her Grandma Lottie used to bring her to see the movies. Lottie would get disoriented in the dusk of the evening light after the movie was over. “She insisted on walking east and I would have to practically drag her to the corner on the west,” Mom remembered. “Once she rounded the corner at the bank, she could remember where she was and we could go home.”

On Foot in the Old Stomping Grounds

So, we decided to get out of the car to let her retrace her own steps to show us, and sure enough, right around the corner, there was the old movie theater, looking for all the world as if it had come right out of the 1940s when Joyce and Grandma Lottie were still watching silent movies inside.

Now on foot, Mom’s pace started to pick up. She walked quickly north for 3 or 4 blocks and then made a left toward what used to be the feed store on the corner of the block where she had lived. And as we passed an old 1900s-style Victorian home—the only residence on this side of the road—we pointed it out to her. She looked only for a moment before exclaiming, “I think that is the Lindsay’s house!” And in that moment, realization dawned. Anthony Lindsay was her childhood nemesis. The naughty little boy who was her best-worst friend. He was the little kid who would knock down the walls of her carefully built playhouse. Now we knew we were almost home.

Here she told the story again of her playhouse being simple piles of dirt she swept up into mounds to form exterior walls. She built windows and doors into the walls of her playhouse as well, and trained her dog, Pal, to go in through the door only, never to step his paws over the carefully formed walls. She looked up and saw the mound of a small hill only 100 yards away and identified it as the place where she spent the bulk of her childhood hours, playing among the rocks and scrubby sagebrush with her imaginary friends, Gagen and Rye.

The home we had come looking for was gone, replaced by a farm fencing establishment, but a few steps further and she knew she was on sacred ground. She could point out other landmarks: towering Cottonwood trees that had provided shade. A little lane that led to the area where her grandmother’s garden had been. She was allowed to take off her shoes in those days and wade in the mud when here grandmother was irrigating the parched soil, but was not allowed to walk up the furrows.

As she told the story, we could picture white-haired Grandma Lottie, known to us only from a couple of black and white photographs, who had been Mom’s most important childhood companion while her parents were away at work all day to earn a living. Grandma Lottie’s house had originally been a grocery store with big front windows, but the Great Depression meant hard times for everyone. Her Grandfather’s habit of letting destitute customers buy groceries on “credit” because they had no way to pay, eventually bankrupted the operation. So, the grocery store became the family’s living quarters, and Lottie lived in the home without running water until Joyce’s dad piped in cold water sometime in the late 1940s.

Mom could remember laying in bed at night, watching the lights of passing cars circle the walls of the dark room.

Now that she had her feet on the ground, Mom didn’t want to get back into the car. Walking the streets of her little hometown was the more efficient way to recall memories.

Carbon County Mining History

We paused near the park to look at several granite obelisks that included the names of miners killed in multiple mine disasters. Often there was the name of a 40-something-year-old man, followed by several young men with the same surname who died in their teens and early twenties, sons we imagined had followed their father into the coal mine to help the family make a living, who had all perished together. It seemed likely that there could not be a single family in the area who had not at some point lost a loved one in one of these horrific disasters. Some accidents killed a handful of men. Some killed hundreds. It was a sobering realization. Those who survived the day-to-day operations in the mines often succumbed in later life from health complications developed from working in the coal mines.

Elementary School

We walked further to the location where her elementary school had stood. She recognized this spot because there, across the street was the old Methodist church where the schoolchildren would go at lunchtime to get hot lunch, a new innovation of the wartime years following the Great Depression. Down the block was the Masonic temple. We continued east toward the neighborhood where her Grandmother Tanner’s home had been.

Townspeople were beginning to line the sidewalks and setting up folding camp chairs for that afternoon’s Homecoming Parade for the high school football team. Hard rock blared from speakers set up in the central intersection of town. I watched these families carefully and wondered what had brought them or their ancestors to settle here.

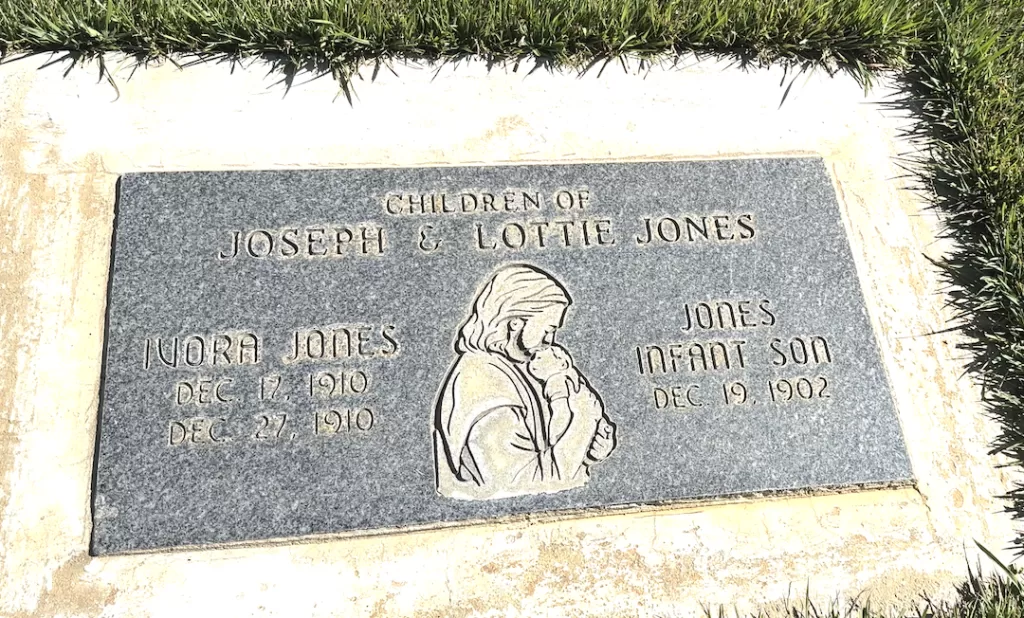

Finally, we got into the car again and drove the last few blocks to the area where she remembered a hospital and a cemetery. The hospital was important because it was where she and four of her siblings had been born. Joyce was the only one of five who had survived. Child-rearing was a risky operation in those days.

The cemetery was exactly where she remembered it should be. Mom could remember that her paternal grandparents’ gravestone was right along the fence line, and as we walked, we recognized names of Mom’s aunts, uncles, and infant cousins. When we couldn’t immediately locate the gravestone of her grandparents, a groundskeeper pointed out a small kiosk that identified which of Joyce’s Tanner ancestors were buried and where, and after a few minutes, she returned with the coordinates of the headstone. It was right along the fence line, just as Joyce had remembered.

There in the grass was the headstone marking the resting place for her grandmother, Johanna Marie Hansen, and her grandfather, James Edwin Tanner. But what I hadn’t known was that part of the pull of the this burial spot was two unmarked plots where the remains of two of Mom’s infant siblings rest: Myrna Lou and baby Tanner. Now I knew I was on sacred ground too.

Mom’s parents left Price when she was about ten. Grandpa Mark had not become a miner. Instead, he had driven a truck loaded with coal up and down the steep and winding canyon roads. Mom could remember traveling with him to haul a load of coal down to the valley. One memorable day, as they dropped into Spanish Fork, she saw an entire field of yellow dandelions, and Grandpa had stopped the truck long enough for her to pick herself a bouquet. For her, dandelions have been beloved ever since.

Mom remembered traveling along Highway 89 to the Wasatch Front and then on to Ravarinos to gas up. Grandpa always stopped at Ravarinos because the first Kentucky Fried Chicken was located on the same block and Grandpa adored Kentucky Fried Chicken all of his life.

There was no opportunity in those days, in this impoverished family, for an advanced education, so Grandpa Mark followed in his father’s footsteps to become a butcher and grocer. The economy didn’t improve much in Price after World War II ended, and he was eventually forced to move his small family to Orem, a larger city, hoping to find work. “I expect that move almost devastated my Grandmother,” Mom stated. “I always knew I was her favorite until I said so at a reunion once and my cousins all disagreed, thinking they were actually Grandma Lottie’s favorite grandchild. She had the ability to make everyone feel uniquely special.”

After lunch, we traveled back down the canyon to stop at the Helper Museum. Mom has always had a special affinity for electric trains, and the museum boasts more than one display. We learned that it is actually much more than a railroad museum. Members of the small community hailed from 25 different countries because Helper became the crossroads of the mines and the railroad, and work was available here. We stepped back in time and explored room after room of preserved historic artifacts that helped us understand more about what it might have been like to grow up in Carbon County, including the model trains we had come to see, and a set of roller skates just like the ones Mom remembered wearing.

We didn’t really hear any new stories. Mom’s memory is sharp, but she usually recalls these same vivid stories and repeats them nearly word-for-word. We have heard these family narratives over and over for most of our lives: the time Uncle Pat discovered Grandpa Jones trapped under a wagon on the farm and somehow lifted the entire wagon box off from his father’s almost lifeless body, then ran several miles back to town to get help.

How Grandpa’s leg had to be amputated and the rest of the family had pitched in to take over his duties as the school custodian in order to preserve the family income.

The time Uncle Owen discovered his young brother, Mark, (our Grandfather) smoking cigarettes behind the kitchen stove and made him smoke the entire pack in an effort to stop the habit before it got started.

How Uncle Roland and Aunt Gerene had raised 12 children in a 2-room log cabin.

How Grandma Seely had given Grandma Ruth and her cousin a prized quarter to go to the county fair, and how young Ruth had gotten into an argument with her cousin and bit her. Grandma Seely bit Ruth back and made her return the quarter as punishment.

The Importance of PLACE

What I learned from the day was a reminder of the sense of place and how important it is to memories. There was a certain romance in standing on the site where my great-grandmother once grew flowers. Seeing the vintage theater where Mom watched wartime movies for a nickel took me back in time too. It made me grateful for this little hardscrabble community that had nurtured Mom’s childhood. I felt reverence at the unmarked grave of an Aunt I had never met. It reassured me that every member of my family is important to our family story—even when we know them only by name. I have the resources Mom’s parents lacked to make sure there is a headstone to mark Myrna Lou and Baby Tanner’s existence, and I think that was the purpose of the trip for me. I want them to know I am grateful to have them in my family.

Mostly, I am grateful that Mom was there to share the day with us. It was a clear, warm October day with a cornflower blue sky. Castle Gate swung wide as we traveled back home.