Harriet Anna Johnson Whiting

As I consider the impact I would like to have in the lives of my own grandchildren, it has been helpful to consider the legacy each of my grandmothers has left to me. This is the first in the series:

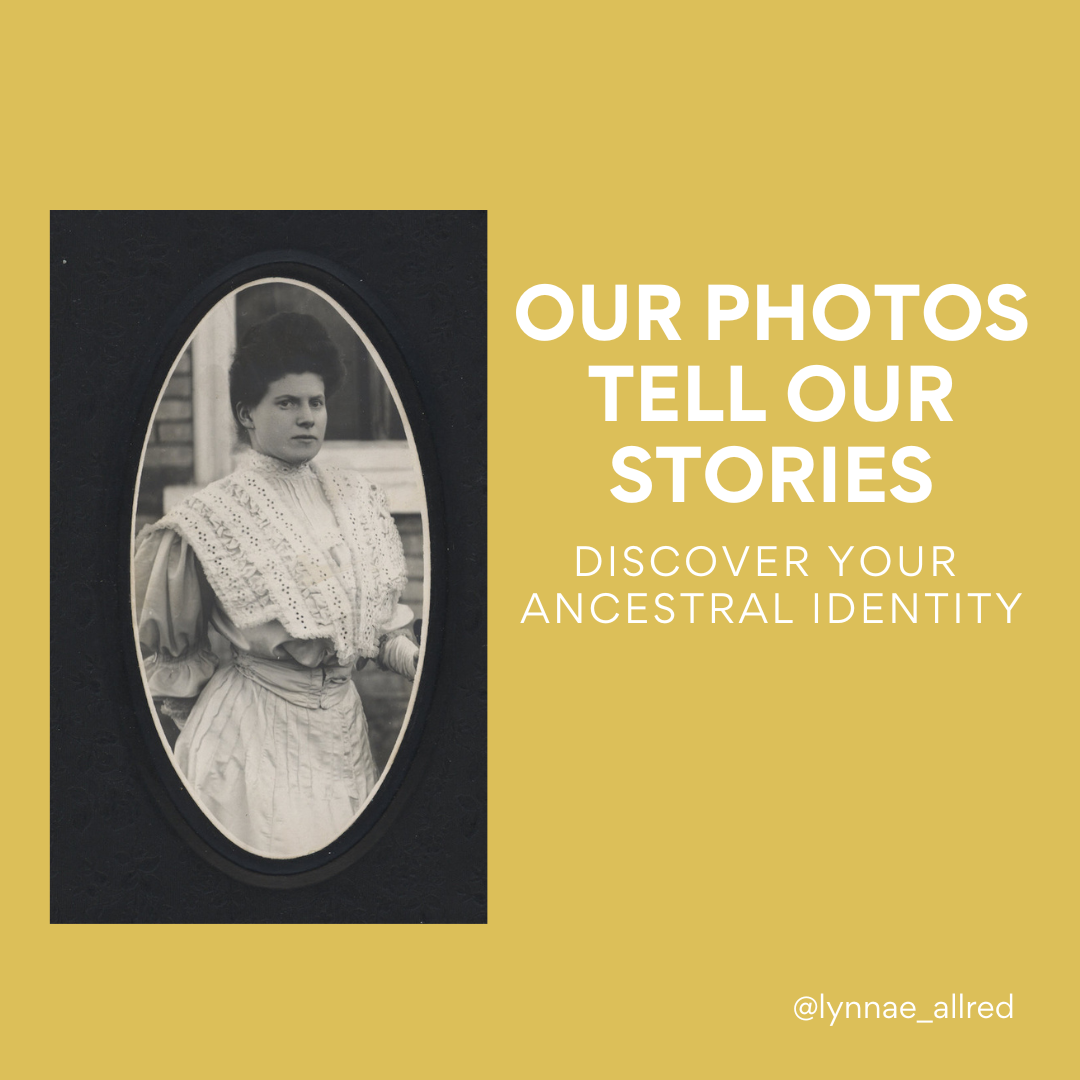

My paternal grandparents kept a large photo of a dark-haired, unsmiling woman above the head of their bed. The woman looked so imposing, I couldn’t understand why Grandma would keep this kind of artwork hanging over her head when she was trying to sleep.

When I was old enough to understand, Grandma and Grandpa explained why this portrait was precious to them. It is a photograph of Grandpa Harold’s mother, Hattie. She died just thirteen days after he was born due to complications of childbirth. The woman I had been so scared of for most of my childhood was my own great-grandmother.

Harriet (Hattie) Anna Johnson Whiting, 1906

For most of my life, that’s all I knew. She looked so severe. She had dark hair and dark eyes. She was a stranger to me otherwise.

I was a young mother with my own children before my father found a document written by one of Hattie’s sisters, Zina. Dad made it available to rest of the family by digitizing it and including the story in a printed family history. The memoir about Hattie was only a few pages long, but it included what had been lacking: stories about Hattie’s life. These little snippets of insight gave me a connection to my great-grandmother.

One of the most important details was that Hattie was an accomplished seamstress and in the photo above, taken on the eve of her wedding, she’s wearing a wedding gown she designed and sewed herself.

The Wedding

Zina wrote at length about the wedding: “The joyous spirit of the evening was climaxed by a dance on the lawn in the moonlight on this crisp but snowless New Year’s Eve. It was a sight never to be forgotten as these young people, dressed in their best, rhythmically wove in and out of complicated formations of square dances to the sprightly music of a harmonica played by a talented musician, while his partner called the changes from a vantage point on the porch. How beautiful, graceful, and radiantly happy Hattie seemed as she and Jim formed the center of these gay dancers.”

One simple story, and Hattie was transformed into an individual I could love.

Zina also wrote: “Shortly after the wedding, Jim left for California where he had work with the Straw and Stores Construction Company…They set up housekeeping in a small house near the camp and here spent several happy months. Hattie made friends with all the neighbors, among them an interesting Japanese lady who became so attached to the young bride that she showered her with gifts, one a real Japanese kimono with all the customary accessories.”

There are hints here about Hattie’s personality. She was friendly. She was radiant. She was adored.

The New Baby

Hattie returned to her parents’ home the following year to deliver her first baby:

“…a son, later christened Harold Johnson Whiting, was born. For four days there was only rejoicing, for both Hattie and the baby were doing fine. Saturday morning, Hattie was not so alert and cheerful. There seemed to be nothing alarming in her condition. It was not until Thursday of the next week that a serious kidney infection became apparent. For four days everything possible was done to combat it…She passed away at 6 a.m. Not only those near and dear to her were stunned, but the whole town. Her funeral was one of the largest ever held in Springville…Stores and schools closed during the services. This in itself was a great tribute to the respect and esteem in which Hattie and Jim were held in the community.”

With only a few lines, Zina had helped me understand something else I had not known. Hattie was not a nobody. She was beloved by her entire community. That is the power of story.

The Grief:

I have often wondered how a young father, recently widowed and employed hundreds of miles away, managed the grief. He had no way to care for a baby, who, according to Zina, “daily grew more thin and pale.” With no other options, he left the infant in the care of Hattie’s mother, Amelia, and bit by bit, Amelia nursed the infant back to health. By the time Jim was ready to remarry four years later, young Harold was as attached to his Grandmother as she was to him, and Jim made the difficult decision to leave his son to be raised by his grandparents rather than disrupt his attachment to Hattie’s family, who had cared for the youngster with such tenderness.

The Story of the Photo

And now the story of the photograph and how it came to hang in my grandparents’ bedroom:

Jim’s second wife, Beulah, perhaps empathetic to the wrenching decision her new husband had just made, arranged to have a portrait made from an enlargement of a family photograph that was taken on the eve of Hattie’s wedding:

Beulah had the photo framed in an elaborate oval frame, then hung it in her living room after she and Jim were married. She wanted to preserve the memory of Hattie for her husband and the 4-year-old son who had no other way to remember his birth mother. I have never fully wrapped my head around the unselfishness of that act, but knowing a second wife would preserve the memory of the first wife in this tender, selfless way has always made me love both women better.

After Beulah’s death, the portrait was given to Harold, and it hung above his bed for the rest of his life. That’s the power of a photograph. This portrait of Hattie is now precious to the entire family, for reasons these snippets of story only begin to explain.

Today, as I look closely at Hattie’s photo, (together with others gathered by family members and archived online where we can all access them), I can see something other than severity in her face. I can look closely and see the shape of her eyes, her nose, her chin, and realize she may have passed these and other features along to me.

Like Hattie, I am the oldest daughter in a family. Like her, I have one older brother, and several younger siblings. I know, from reading Zina’s stories about Grandma Hattie, that we each took on similar roles in the family hierarchy. I suspect that is part of why I have always felt so drawn to her, and why the emptiness of not knowing anything about her bothered me so much when I was young.

Today, I carry her DNA. She is part of me. Knowing her more deeply helps me feel more complete. She has become my Great-Grandmother. Knowing just a little of her story has made her come alive, and in the process, has given me a precious piece of my own identity.